Beyond the Drunken Bricklayer - Modern British Glass

Beyond the Drunken Bricklayer – British Glass and Modern Design

Britain has a long history of quality glass manufacturing dating back to the late seventeenth century. We are probably best known for our early contributions in developing high quality lead crystal and skilfully created heavy cut glass designs. When we think of British glass it is probably Georgian wine glasses and decanters or perhaps intricate Victorian Vaseline or uranium vases that come most to mind rather than modern, let alone modernist designs.

In recent years, though, one of the most collectable forms of British glass has come from the London-based factory of Whitefriars. I am referring to the textured and coloured moulded glass vessels designed by Geoffrey Baxter in the late 1960s. His so-called drunken bricklayer vases, banjo vases and other shapes, all released in a range of different colours, have become iconic of the pop culture design of the 1960s and these are some of the most collectable of British glass. They are certainly modernist in their design and aesthetic.

Fine though these pieces are, we think it is worth digging a little deeper to see if there is more to modern British glass design than this well known output. An initial glance at the displays at antique fairs and shops might suggest otherwise. It is true that glass design in Britain has been rather traditional for much of the period after 1870. If the general reference books are to be believed glass barely figures as a medium for arts and crafts design. There are a few noted designs by Christopher Dresser for Clutha glass in Glasgow, some nice pieces by Harry Powell for Powell and Sons (Whitefriars) and a few fluid Art-Nouveau designs by Stuart and Sons, John Walsh Walsh and Stevens and Williams but compared to what was happening in continental Europe this is a very limited output. We had nothing to compare with Galle, Daum, or Lalique at this time. And our engraved glass from this period looks tame in style compared to the contributions coming from Sweden or Czechoslovakia in the first few decades of the Twentieth Century.

Things don’t get much more exciting with the development of Art Deco designs. Keith Murray, better known for his ceramic designs for Wedgwood, designed some interesting cut glass for Stevens and Williams, there are a few rare pieces for Webb Corbett by the artist Paul Nash and again Whitefriars probably led the way with the work of William Wilson and Barnaby Powell. But Britain was always hesitant to embrace the Art-Deco style.

Post-war the centres for modernism were not London or Stourbridge but Murano in Italy, Finland, Sweden and Czechoslovakia. Britain came late and somewhat tentatively to modernism. As well as Britain’s slow emergence from post-war austerity which did much to stifle design innovation in the immediate years after the war, this was probably also because most glass design and the major factories looked back to the traditional designs of the Georgian and Regency periods.

The vast quantity of cut crystal dominated Britain’s output through the Twentieth Century. Made with undoubted fine materials and great cutting skills, these pieces cannot often be said to have been at the forefront of design. And, unlike some of the European factories that employed Art School educated designers as their artistic directors to lead a design revolution, the British factories left design in the hands of the managers and the skilled cutters and blowers who didn’t have the design knowledge or awareness of artistic trends.

When Britain did begin to take note of modern design it was often heavily influenced by developments elsewhere. Much of the output from Whitefriars post-war makes a strong nod to the designs of Scandinavians like Kaj Franck, Tapio Wirkkala, Asta Stromberg and Vicke Lindstrand.

But dig a little deeper, look beyond the ocean of traditional cut glass that adorned the tables and window sills of everyone’s Grandma and Great Aunt, and you can find a tentative but interesting embrace of modernism.

With this small exhibition we aim to introduce you to some of the more modern designs in glass that were produced in Britain. Our focus is on the period from about 1935-85. We have focused, in particular, on those bastions of traditional design cut and engraved glass to show that there was some forward thinking happening on these shores. We also add some of the modern design influences that started to emerge in new studios and factories from the 1960s such as Caithness, Dartington, and Kings Lynn. While well-known figures like Geoffrey Baxter are featured here, though not for his most well-known output, our aim is to showcase other, perhaps less-well known designers. From the early years of this period we include the work of Clyne Farquharson. Post-war you will find important contributions including by David Hammond, John Luxton, Domhnall ÓBroin, Colin Terris, Frank Thrower and Ronald Stennett-Wilson. This is not an exhaustive list and there is much more still to be researched but we hope this small exhibition does enough to convince you of two things: that Britain did produce modernist designs in glass.

We have not included the studio glass that emerged as part of a design movement in Britain from the 1970s onwards. That is a big subject in its own right and, perhaps, one for another time.

All the pieces shown here are for sale unless otherwise stated. We will be showcasing these pieces at the Art and Antiques for Everyone fair at the NEC, Birmingham 7-10th April and simultaneously on our website. We aim to add to this section on the website regularly from now on.

Art-Deco

A number of British glass maker produced Art-Deco style designs in the 1930s including Royal Brierly/Stevens and Williams, John Walsh Walsh, Stuart and Sons and Webb Corbett. In most cases this work came from art-school trained artists and designers such as Keith Murray, Clyne Farquharson, Ludwig Kny, and even the prominent artist Paul Nash. The strongly geometric shapes and patterns were influences by the French style of this period.

John Walsh Walsh

Clyne Farquharson leaf pattern large cut glass vase for John Walsh Walsh. Signed on the base NRD 41 (National registered designer 1941).

Clyne Farquharson leaf pattern small cut glass vase for John Walsh Walsh. Signed on the base and dated 1938.

Clyne Farquharson (1906-78) was a glass designer best known for the Art-Deco glass designs he produced for John Walsh Walsh glassworks during the 1930s. He originally trained in Birmigham at Mosley Road School of Art in 1924. He worked at Walsh Walsh until their closure in 1951. Along with others like Keith Murray, Ludwig Kny and William Wilson he was one of the leading figures in developing art-deco glass in Britain in the 1930s.

Post-War Modernism

Britain’s recovery after WWII was slow and difficult. Attempts to kick-start a modernist design refresh began with the Britain can Make it Exhibition in 1946 and more famously with the Festival of Britain in 1951. Most design-led items in this period were made for the export market in order to help Britain overcome its balance of payments challenges resulting from war-time debts. Only in the late 1950s and especially in the 1960s did modernist design really get a foothold. By this time such a design revolution was fully established in the Scandinavian countries, especially in Finland, Sweden and to a lesser extent Denmark. Glass studios like Orrefors, Kosta, iittala, Nuutajarvi and Holmegaard led the way in the development in glass design in this era.

Many of the pioneers of modernism in Britain and Ireland such as Geoffrey Baxter, Ronald Stennett Wilson, Frank Thrower and Domhnall ÓBroin were either influenced or spent some time in one of the Scandinavian countries absorbing some of their clean line, biomorphic and simple shapes, patterns and colours. They brought these back to Britain to established glass works like Whitefriars or newly opened ones like Caithness, Dartington and Kings Lynn. Even the established factories in Stourbridge such as Thomas Webb, Stuart and Sons and Webb Corbett had their Scandinavian influenced designers such as David Queensbury and John Luxton.

As well as new shapes and colours, the modernist style was also used to revive the more traditional areas of glass production such as cut and engraved glass. Commemorative glass and works for ecclesiastical patrons like Covenry cathedral were often the medium for such designs with people like David Hammond and John Hutton leading the way.

Kings Lynn/Dartington/Wedgwood.

Two Ronald Stennett Wilson small conical paperweights with internal bubble design. The simplicity of these suggests they could be from Stennett Wilson's time at Kings Lynn though this was a design he continued to use during his time at Wedgwood in the 1970s. Unsigned.

Ronald Stennett Wilson Sheringham candlestick with three disks for Wedgwood 1970s. A famous designs that ranges from one to seven disks.

Ronald Stennett Wilson decanter and stopper designed for Wedgwood 1970s. Factory mark etched to base.

Ronald Stennett Wilson swirl green candleholders for Wedgwood. 1970s. Factory mark edtched to the base.

Ronald Stennett Wilson (1915-2009) was one of the leading figures in post-war British glass design. He had a varied career as a journalist, salesman, Army captain during WWII, furniture designer and author on glass design. After the war he was strongly influenced by the modernist style in glass design coming from Sweden. He did much to introduce it to the British public from his sales work at Wuidart and Co. He later began to design and sell his own glass designs. In 1969 he set up a Studio in Kings Lynn in Norfolk. Its early success led to the studio and its designs being bought out by the ceramics company Wedgwood who were diversifying into the glass market. Stennett Wilson worked for wedgwood Glass until he retired in 1979. His Scandinavian inspired modern style was hugely influential on other glass designers in Britain from the 1960s onwards.

Frank Thrower Brutus vase for Wedgwood in original box, 1980s.

Frank Thrower glass vase for Wedgwood. 1980s.

Frank Thrower (1932-87) was the founder and deigner for Dartington Glass which he established in 1966. He had prioviously worked with Ronald Stennett Wilson and, like, him was influenced by the designs in glass coming from the Scandinavian counties in the post-war years. Dartington was bought by Wedgwood Glass in 1982 and they continued to produce many of Thrower's designs. He specialised in moulded glass designs.

Thomas Webb and Sons

David Hammond tall, footed engraved glass vase with dragon design commemorating the Investiture of the Prince of Wales in 1969. An award winning design. This vase is fully signed, numbered #2/50 and comes in the original box with the original certificate.

David Hammond engraved glass vase commemorating the opening of the new Coventry Cathedral for Thomas Webb c1960s.

David Hammond (1931-2002) trained in Stourbridge and at the Royal College of Art. He began working at the established Stourbridge glassmaking firm of Thomas Webb in the early 1950s. This was interrupted by his national service. He returned there in 1956. He specialised in intaglio and engraved glass though also designed some freeform vases very much in the Scandinavian style. He worked for Thomas Webb for over 30 years before retiring in 1986.

Caithness Glass

Domhnall ÓBroin Morvern decanter with stopper in peat colour. Unsigned. With original Caithness and Design Centre stickers. Model 4025 c1964. This was designed to be used with whisky. The hollow stopper serves as a dram measure.

Three cylindrical glass vases by Domhnall ÓBroin for Caithness Glass. Colours are heather, peat and moss. These were one of ÓBroin's earliest Caithness designs and remained in production until the 1970s.

Domhnall ÓBroin (1934-2005) was born in Ireland and started his career at Waterford Crystal in Cork. He also spent some time at Orrefors in Sweden. In 1962 he was recruited as the leading designer at the newly opened Caithness Glass studio in Scotland. He went on to produced a range of Scandinavian influenced designs in a limited palate of colours influenced by the Scottish landscape (Peat, heather, loch, and moss as well as colourless glass). He moved to the USA in 1966. His work at the Caithness studio helped to establish them as one of the leading British glass factories in the latter part of the Twentieth Century.

Colin Terris engraved chalice for the 1972 Munich Olympics for Caithness Glass. Signed and numbered #27/500.

Colin Terris (1937-2007) trained in Edinburgh and joined Caithness Glass in 1968. He started out focusing on engraved glass but latter became best known for his paperweight designs.

Whitefriars Glass

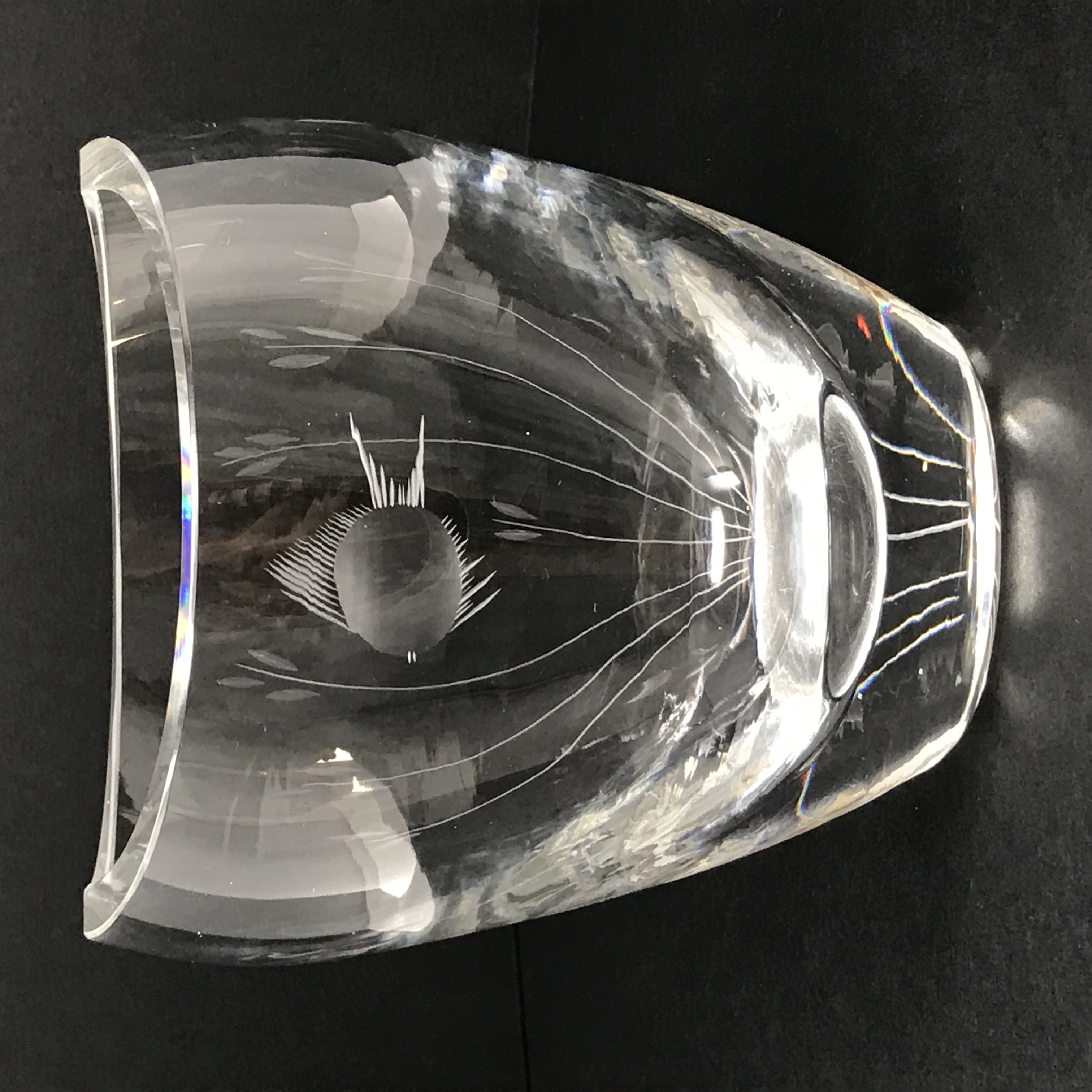

Geoffrey Baxter engraved glass vase with fish design for Whitefriars, catalogue no. C526, 1964. All Whitefrairs glass from this period was unsigned.

Geoffrey Baxter engraved glass goblet commemorating the marriage of Princess Anne to Captain Mark Philips in 1973. Signed, numbered #187/350 with original box and certificate.

Geoffrey Baxter (1922-95) has become the biggest name in post-war British glass largely because of his famous 1960s textured shaped glass vases such as the so-called drunken bricklayer vase and banjo vase. He started at Whitefriars in 1954 and stayed there until the factory closed in 1980. He had studied at the Royal College of Art. He worked alongside the established designer William Wilson and catalogues from that time show the designs by both me. His early designs were strongly influenced by Scandinavian glass design. he began to give his designs a more distinctive British twist culminating in the textured shaped vases that were first released in 1967 and have become icons of sixties pop culture design.

Stuart and Sons.

Large cut glass vase with prism pattern. Stuart Crystal mark to the base. Attributed to John Luxton. Luxton did not sign his pieces but the cut circles and lenses are consistent with his style.

Small cut glass vase with prism pattern. Stuart Crystal mark to the base. Attributed to John Luxton. Luxton did not sign his pieces but the cut circles and lenses are consistent with his style.

Medium cut glass vase with flower pattern. Stuart Crystal mark to the base. Attributed to John Luxton. This piece is reminiscent of the earlier style of Charles Rennie Macintosh. His work became popular again and was much copied in Britain in the 1980s and 90s. We would date this piece to then.

John Luxton (1920-2013) trained as a designer in Stourbridge and then at the Royal College of Art. He worked at Stuart and Sons in Stourbridge from 1948 until retirement in 1985. He also produced some designs as a consultant for them in the 1990s. He specialised in cut glass designs and developed a modern, contemporary style of circles, lenses and elliptical shapes that give his work a modern feel. Most of the designs done at Stuart after the Second World War are attributed to him unless there is a known other designer. His work is now starting to get the recognition it deserves.

Webb Corbett

Len Green Grasses pattern cut glass vase for Webb Corbett, England. Signed with Factory marks and date year 66. A good example of a contemporary style of cut glass from the 1960s.

© Haresfur.co.uk

References

Nigel Benson and Jeanette Hayhurst (2003) Art Deco to Post Modernism – A Legacy of British Art Deco Glass, London: Liber Vitreorum Publications.

Diane Bilbery (ed.) (2019) Britain Can Make It: The 1946 Exhibition of Modern Design, London: Paul Holberton Publishing.

Wendy Evans, Catherine Ross and Alex Werner (1995) Whitefriars Glass: James Powell and Sons of London, London: Museum of London.

Margaret Garlake (1998) New Art New World: British Art in Postwar Society, New haven: Yale University Press.

Charles Hajdmach (2009) 20th Century British Glass, London: Antique Collector’s Club.

Mark Hill (2011) Caithness Glass: Loch, Heather, Peat, London: Mark Hill Publishing.

Lesley Jackson (1991) The New Look: Design in the Fifties, London: Thames and Hudson,

Lesley Jackson (ed.) (1996) Whitefriars Glass: The Art of James Powell and Sons, Shepton Beauchamp: Richard Dennis.

Eric Reynols (1999) The Glass of John Walsh Walsh, 1851-1951, Shepton Beauchamp: Richard Dennis.

Ronald Stennett-Wilson (1975) Modern Glass, London: Studio Vista.

Eve Thrower and Mark Hill (2007) Frank Thrower and Dartington Glass, London: Mark Hill Publishing.